Your Cart is Empty

This is

the story

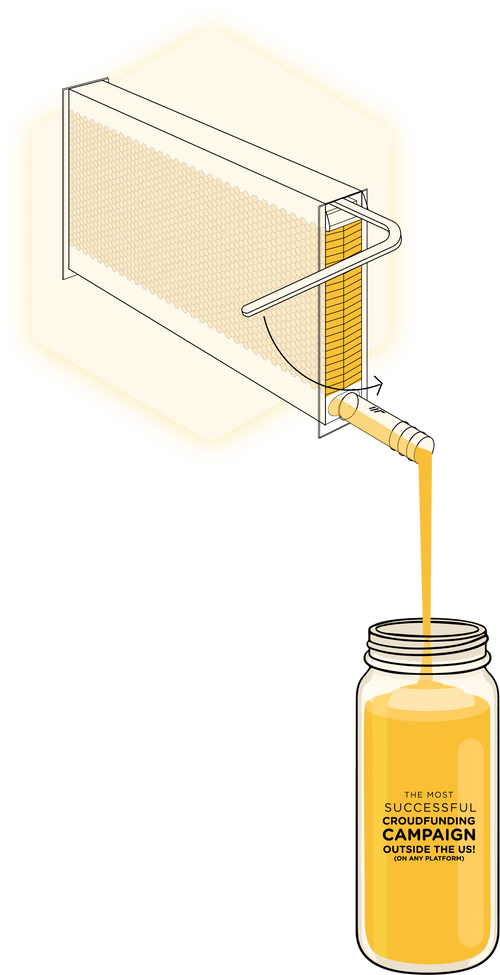

Of how a pair of father and son inventors changed the face of beekeeping and pulled off one of the most successful crowdfunding campaigns in history…

As a third-generation beekeeper who first opened a beehive at six years old, every time Cedar Anderson found himself spending hours of messy sticky hard work harvesting honey, he would say to himself...

There

has to be a better way

Growing up in an alternative community on the east coast of Australia near Byron Bay, my dad Stu was very encouraging as I built all sorts of contraptions.

He and his dad kept bees, so it wasn't a surprise that I'd also inherited the beekeeping bug.

Harvesting honey was such hard work, and always involved squashing lots of bees. I set out to solve the puzzle of getting honey out of a beehive without opening it.

After 10 years of inventing and trying out countless ideas, there was finally a breakthrough.

I had an idea of forming a matrix of hexagonal cells that could be split apart in some way to let the honey flow out.

The next prototypes showed promise... Then Stu had the next 'eureka' moment - what if the cells could come apart vertically? We raced to the shed and built another prototype.

The concept worked!

With our new invention it was now possible to harvest honey from a beehive quickly and easily, without disturbing the bees and without requiring a honey shed or special extraction equipment. We were convinced that our invention could change beekeeping forever. Now it was time to introduce the Flow Hive to the world.

Campaign launched

22 February, 2015

One of the largest crowdfunding campaigns

in the world!

Watch ABC

Australian Story

We also have world wide recognition

GOOD DESIGN AWARD

PRODUCT OF THE

YEAR 2016

APIMONDIA

SILVER MEDAL - WORLD BEEKEEPING

AWARDS 2017

D&AD IMPACT

WHITE PENCIL

URBAN LIVING 2016

FAST COMPANY

WORLD CHANGING IDEAS AWARD 2017 WINNER CONSUMER PRODUCTS

NSW BUSINESS CHAMBER

BUSINESS AWARDS

2017 STATE WINNER

Supporting ‘newbees’

To give our customers the best possible start in the fascinating art of beekeeping, we created a range of free educational resources and later launched TheBeekeeper.org, an online learning platform with 50% of profits used to protect pollinator habitat worldwide.

Regenerate

As my dad and I navigated the shift from tinkering in a shed to heading our company, Flow, we were determined to use the business as a means of achieving positive things in the world.

Empower

From the beginning, Flow has been about more than just beehives or honey. As the company has evolved, our mission has remained the same – “to have a regenerative impact on the planet through innovation in beekeeping that inspires, empowers and connects”.

B sustainable

In 2018 we were certified as a B Corp, solidifying a commitment to meeting the highest standards of social and environmental performance. We use materials that are as ethically and sustainably sourced as we can, and our factory runs on 100% solar power, turning sunbeams into laserbeams that cut wooden panels.

j

j